November 18, 2012 Gordon Chang

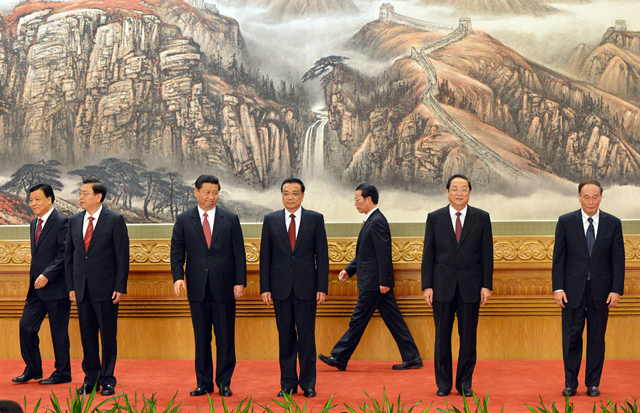

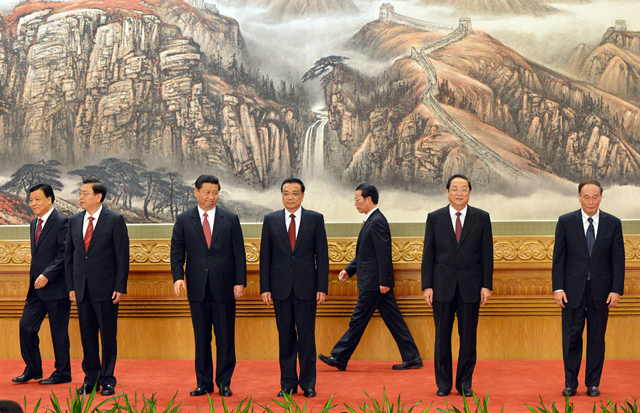

On Thursday, Chinaˇ¦s Communist Party revealed its leadership lineup for the next five years as seven men, most of whom oppose reform, walked out from behind a curtain in Beijing. If they fail to restructure the Chinese economy soon, however, the Peopleˇ¦s Republic will not be able to sustain itself.

At least fourˇXand maybe as many as sixˇXof the new Politburo Standing Committee are so-called ˇ§conservatives.ˇ¨ In the Chinese context, this means they are not predisposed to stopping the backward drift evident in Beijing since the middle of 2006. Then, Hu Jintao began to undo the legacy of Deng Xiaoping, whose transformational policies were encapsulated by the phrase ˇ§reform and opening up.ˇ¨

Huˇ¦s policy of closing the country down was popular inside Beijing for many reasons, but it became Chinaˇ¦s new paradigm because it had the support of what David Shambaugh calls the ˇ§Iron Quadrangle,ˇ¨ state-owned enterprises, the security apparatus, the Peopleˇ¦s Liberation Army, and Communist Party conservatives. ˇ§The coalition of these four power interest groups ˇĄcapturedˇ¦ Hu, who was too weak and disinclined to stand up to them, and they stalled reforms,ˇ¨ writes the noted George Washington University professor. Others define the constituent elements of the conservatives differentlyˇXmany identify ˇ§powerful familiesˇ¨ as being inside this circle of power, for instanceˇXbut itˇ¦s clear that entrenched interests now dominate politics in the Chinese capital.

There is only one known reformer in the new Standing Committee, No. 2-ranked Li Keqiang, who is slated to take over from Wen Jiabao as premier next March when government posts change hands at the annual National Peopleˇ¦s Congress meeting. Yet Li is a slim reed of hope for positive change. He made his way onto the Standing Committee only because of his close political connections with Hu JintaoˇXboth come from the Communist Youth League faction of the PartyˇXand has so far left a trail of only mediocre accomplishment on his way to the top.

Apart from Li, the Standing Committee looks reactionary. The No. 3 leader is a North Korea-trained economist, Zhang Dejiang. Zhang will almost certainly represent the interests of state enterprises in future deliberations. The member slated to get the economics portfolio is the last-ranked Zhang Gaoli, another defender of vested interests. He is expected to block any reform initiatives that Li Keqiang may hatch.

Observers had hoped that Wang Qishan, an especially capable finance and economics troubleshooter, would get some economics role, but that would have been too logical. Wang ended up in charge of anti-corruption efforts as head of the Partyˇ¦s Central Commission for Discipline Inspection. The universal assessment is that this position is ˇ§a huge wasteˇ¨ of Comrade Qishanˇ¦s considerable talents.

One man, the 86-year-old Jiang Zemin, seems to have packed the Standing Committee, the apex of political power in China. With no official position, the former supremo appears to be the most powerful Chinese politician, surpassing both Xi Jinping, the newly anointed general secretary, and Xiˇ¦s predecessor, Hu Jintao. Jiang, who as Deng Xiaopingˇ¦s successor generally favored reform, is now protecting his familyˇ¦s business interests as well as the interests of others who have become fabulously wealthy in recent years.

Is all lost? Li Jiange, chairman of China International Capital Corp., predicts General Secretary Xi will introduce economic reforms in late 2013 to reduce Beijingˇ¦s role in the economy and break up state monopolies. These changes would be welcome, of course. Growth is slowing partly because state entities are using their clout to close off opportunities for the most productive actors in the economy, domestic entrepreneurs and foreign companies.

South China Morning Post columnist Victoria Ruan also believes Xi Jinping and Li Keqiang are hoping to launch ˇ§bold reforms to sustain growth over the next decade,ˇ¨ but she thinks the pair ˇ§for the short termˇ¨ is ˇ§likely to be busy consolidating power and maintaining political stability.ˇ¨ In other words, Xi and Li are in no position to sponsor change soon.

China has progressed about as far as it can within its existing political framework. Further reform would threaten the Communist Partyˇ¦s hold on power, so it will not sponsor change of that sort. As Minxin Pei of Claremont McKenna College has pointed out, a market economy requires the rule of law, which in turn requires ˇ§institutional curbsˇ¨ on government. Because these two limitations on power are incompatible with the Partyˇ¦s ambitions to continue to dominate society, China cannot make much progress toward them within the current system. China, Pei has argued, is now trapped.

Today, there is a growing recognition that fundamental economic restructuring in China cannot occur unless there is far-reaching political reform, certainly more ambitious than the ˇ§inner Party democracyˇ¨ that leaders talk about. Yet meaningful political reform is completely off the table, as the disappointing lineup of the new Standing Committee makes clear.

China, for the moment, is trapped in various self-defeating loops. In one of these, a slumping economy is creating a crisis of legitimacy. The legitimacy crisis, in turn, is causing a wide-ranging political crackdown. The crackdown makes reform impossible. The lack of reform prevents long-term economic growth.

China has been caught in such situations before but has managed to implement critical reforms. That happened at the end of 1978, for instance, when Deng Xiaoping launched more than three decades of growth.

But the conditions for reform that existed then do not exist now. Then, the country had one strong leader. Now, however, it does not. Each leader of the Peopleˇ¦s Republic has been weaker than his predecessor. Many think this progression from one-man to collective rule is progress, and in many ways it is. Nonetheless, at this moment China needs someone with the vision, guile, and clout to break the ˇ§Iron Quadrangle.ˇ¨ There is no such individual on the Standing Committee, and none can be found in lower levels in Beijing.

Yet in China, in some small village or large city, there is a charismatic individual waiting. He or she is probably not in the Communist Party but in any event has no intention of preserving the existing system. We can all guess what happens next.